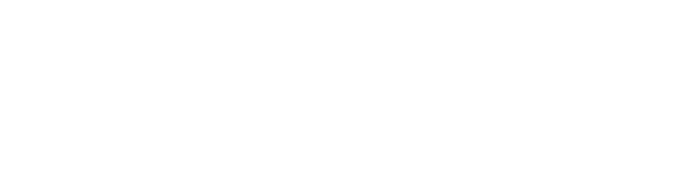

I. Un rumor en la selva (COSTA RICA)

Al caer la tarde en el delta del Diquís, el aire se espesa con los insectos y el olor dulce del banano. Entre la niebla baja, hay sombras que no pertenecen a los árboles. Son redondas, exactas, silenciosas. No son fruto del capricho de un río ni de un terremoto antiguo. Son esferas. Centenares de esferas de piedra, algunas del tamaño de una pelota, otras como un auto pequeño, pulidas hasta la obstinación. Nadie sabe con certeza por qué están ahí.

Costa Rica, país de volcanes y cafetales, guarda en su extremo sur una historia que a veces parece inventada. Las primeras noticias modernas de las esferas surgieron a finales de la década de 1930, cuando cuadrillas que abrían paso a plantaciones bananeras toparon con rocas perfectas enterradas a medias, dispuestas en alineaciones que se perdían entre los juncos. Les dijeron “bolas” y las apartaron con maquinaria sin sospechar que estaban empujando siglos de memoria. Algunas se rajaron, otras fueron rodadas hasta jardines privados o plazas capitalinas. Las más afortunadas quedaron donde nacieron, como ojos de basalto que no parpadean.

A estas alturas, el lector querrá saber: ¿quién las hizo? ¿cómo lograron esa perfección? ¿qué significaban? El misterio empieza por lo poco que podemos afirmar con seguridad. Sabemos que su manufactura pertenece a los cacicazgos del Diquís, sociedades complejas que florecieron entre los siglos VI y XVI. Sabemos también que fueron talladas sobre todo en gabro—una roca dura como la paciencia—y en menor medida en arenisca y granodiorita. Pero más allá de lo técnico, las esferas parecen resistirse, con una elegancia antigua, a la obediencia de las explicaciones.

II. La geometría de lo imposible

Imagine un artesano de hace mil años sosteniendo un martillo de piedra frente a un bloque oscuro extraído de las colinas. No hay metales, no hay poleas de acero, no hay torno. Hay, en cambio, tiempo. Mucho tiempo. Golpear, picar, girar; frotar con arena húmeda hasta que la superficie ceda su aspereza. Algunos investigadores proponen que se usaron núcleos duros para “pecking”—picoteo sistemático—y abrasivos de río para pulir, quizá aplicando calor para fracturar microimperfecciones. Es un proceso que no concede atajos. La esfera es la forma más exigente: cualquier exceso, cualquier descuido, delata la mano.

Sin embargo, muchas de las esferas conservan una esfericidad que raya en lo obsesivo. Las mayores alcanzan más de dos metros y medio de diámetro y pesan tantas toneladas que su sola movilidad exige organización, logística y propósito. Aquí aparece otro secreto: las esferas no estaban, por regla, solas. Los hallazgos arqueológicos hablan de conjuntos, de círculos kilométricos, de alineaciones que apuntan a direcciones precisas. ¿Eran mapas del cielo? ¿Ejes de poder? ¿Marcas de territorio? ¿Instrumentos para ordenar el mundo?

La geometría no es inocente. Un círculo trazado en tierra llama y ordena. Una esfera instalada frente a una casa de cacique indica algo que cualquier visitante comprende sin hablar: aquí hay jerarquía. Aquí hay centro. Aquí—dirían los cronistas si hubieran llegado a tiempo—se articula una comunidad.

III. Alineaciones y silencios

III. Alineaciones y silencios

Todavía hoy, cuando uno llega a Finca 6, Batambal, El Silencio o Grijalba-2—sitios del extremo sur que resguardan esferas en su contexto original—percibe una intencionalidad que no cabe en la casualidad. Las piedras, semienterradas, parecen emerger de la tierra como burbujas detenidas. Se alinean hacia cerros específicos o hacia el curso del sol en momentos señalados. No es gratuito pensar en calendarios, aunque la ciencia sigue pidiendo cautela: hay alineaciones, sí; hay patrones, sí; pero convertir esos patrones en un calendario solar requiere un cuidado que solo el tiempo y más hallazgos garantizarán.

Mientras tanto, el silencio. El Diquís—nombre quechua que se adhirió al río Térraba como un eco ajeno—conserva una música de agua y pájaros que vuelve razonable la hipótesis de la ceremonia. ¿Y si las esferas fueran puntos de reunión? ¿Si marcaran procesiones? ¿Si su circularidad buscara imitar la completitud del cosmos, cerrar un diálogo entre el cielo y la tierra? En muchas culturas, lo redondo señala lo sagrado, lo total, lo que no tiene aristas. No es descabellado suponer que aquí también.

Pero el misterio no es solo cosmológico. Es también humano. ¿Cuántas manos, cuántas generaciones tardaron en tallar el catálogo de esferas que hoy conocemos? ¿Cuántos aprendizajes pasaron de un taller a otro, cuántas técnicas desaparecieron en los fuegos de la conquista, cuántas historias se contaron alrededor de estas piedras cuando la noche era menos distraída? Tal vez ahí reside su magnetismo: donde hay piedra, hay paciencia. Y donde hay paciencia, hay relato.

IV. Oro por dentro: leyendas y heridas

La perfección provoca tentaciones. En la primera mitad del siglo XX, la leyenda de que las esferas guardaban oro en su interior se extendió como pólvora húmeda. Hubo quienes las abrieron a golpes, quienes las dinamitaron, quienes las partieron con la misma facilidad con que se rompen los silencios. Dentro, por supuesto, solo había roca. Cada cicatriz cuenta la historia de un asalto. Ver una esfera agrietada es como mirar un mapa de la avidez humana.

No es la única herida. Muchas esferas fueron trasladadas—algunas a ciudades, otras a patios privados—donde cambiaron de sentido: pasaron de ser hitos ceremoniales a convertirse en ornamentos. La distancia entre esos dos destinos resume nuestro desconcierto moderno. Siempre que un objeto sagrado acaba entre macetas, no es el objeto el que se degrada; somos nosotros, que perdimos el manual para leerlo.

Afortunadamente, el país ha ido reconciliándose con sus piedras. Hay museos que las devuelven al contexto, comunidades que las resguardan, leyes que las protegen. Hay, sobre todo, preguntas que ya no buscan la anécdota del tesoro sino la trama más honda: ¿cómo encajan las esferas en la gran historia de los cacicazgos del sur? ¿Qué nos dicen sobre la administración del poder, sobre el intercambio, sobre la astronomía empírica, sobre la estética precolombina?

V. La ceremonia de mirar

Una esfera no se lee: se mira. Y mirarla es participar, aunque sea a destiempo, de la ceremonia para la que fue hecha. Uno se acerca y comprueba que no es absolutamente perfecta; descubre pequeños planos, marcas antiguas de impacto, zonas más rugosas. El ojo moderno, acostumbrado a la exactitud industrial, encuentra una perfección más difícil: la perfección suficiente. La que basta para que el brillo de la superficie capture la luz, para que el borde dibuje una línea continua contra el verde, para que el volumen imponga su presencia sin decir palabra.

Frente a ella, el visitante entra en un pacto. La esfera le promete continuidad—todo punto del borde se prolonga en una curva sin fin—y le exige paciencia—si quiere entender algo, tendrá que quedarse un rato, rodearla, sentir su escala, escuchar los insectos. En un mundo que corre, el Diquís propone un verbo distinto: permanecer.

Tal vez por eso las esferas se han vuelto, además de patrimonio, una ética. En tiempos de prisa, aceptar una roca redonda como maestra no es poca cosa. Nos recuerda que la belleza puede ser una función de la constancia y que la memoria, cuando no se escribe, necesita formas más tercas para sobrevivir.

VI. Hipótesis en círculo

VI. Hipótesis en círculo

El archivo de teorías es amplio y, a veces, pintoresco. Las hay que ubican las esferas como nodos de navegación terrestre, como líneas de vista entre poblados, como marcadores funerarios. Otras sugieren usos acústicos, como resonadores para rituales; el mito urbano de que actúan como brújulas o que “pierden peso” en ciertas lunas llena, si bien literario, carece de evidencia. Las hipótesis más sólidas las sitúan como símbolos de prestigio y poder, integradas en plazas y conjuntos arquitectónicos de los cacicazgos, quizá con correlatos astronómicos. Es decir: no eran solo esculturas; la escultura era parte de un sistema.

La arqueología, así, no tanto resuelve como estrecha el cerco. Hoy sabemos más sobre dónde estaban y con qué se hicieron que sobre su “por qué” último. Y quizá esa sea la mejor noticia: un misterio no es un agujero; es un horizonte.

VII. El lenguaje de la esfera

Si pudiéramos traducir la voz de la piedra, ¿qué diría? Tal vez contaría el origen de la materia: gabro enfriado lentamente bajo un volcán, subido después a lomo de mundo hacia la luz. Tal vez contaría de las manos que la buscaron en la montaña, la hicieron rodar con troncos y cuerdas por senderos que ya no existen. Tal vez se reiría de nosotros—tan convencidos de que todo debe tener una utilidad inmediata—y nos pediría una tarde sin teléfonos para intentar lo obvio: estar a su lado.

Hay en la esfera un lenguaje que reconocemos sin haber estudiado: el de lo completo. En sociedades que enfrentaban el mar, la selva y el volcán, construir una forma que niega el accidente es un gesto poderoso. La esfera afirma lo que no cambia, incluso cuando el entorno es puro cambio. Es un mensaje de orden en mitad del caos, una flor de piedra que no se marchita.

VIII. Volver al sitio

Quien quiera escuchar ese lenguaje debe ir al sur. No basta con ver una esfera trasladada a una plaza; hay que pisar el barro que la rodea en su casa original. En Finca 6, por ejemplo, las huellas arqueológicas de viviendas y plazas acompañan a las piedras, devolviéndoles el coro que habían perdido. En Batambal, el paisaje abierto permite entender la escala del gesto: en una llanura tan vasta, ¿cómo no buscar marcas para el nosotros?

El viaje no solo es geográfico. Exige un desplazamiento interior: pasar del afán de “explicarlo todo” a la paciencia de “entender algo”. En ese tránsito, el misterio no se disuelve; se vuelve compañía. Y la esfera, que parecía muda, se convierte en una maestra discreta.

IX. Epílogo: lo que no sabemos (todavía)

Quizá nuestra época—tan enamorada de la respuesta—se impacienta ante lo que no puede clausurar. Pero hay misterios que conviene preservar, no por ignorancia sino por respeto. Las esferas del Diquís nos enseñan que el pasado puede ser exacto sin ser transparente, que la belleza puede negarse a ser utilidad, que una comunidad desaparecida aún puede dictar lecciones de forma y sentido.

Cuando el sol se pone y las sombras vuelven a ser de los árboles, las esferas quedan ahí, respirando su silencio. Mañana hubiera sido ayer para ellas. Y pasado mañana también. Mire otra vez: parecen moverse cuando se marcha la luz. No se mueven, claro; somos nosotros, que por fin empezamos a girar a su ritmo.

Recuadro: datos para el viajero curioso

-

Dónde: Delta del Diquís, cantón de Osa, sur de Costa Rica. Sitios clave: Finca 6, Batambal, El Silencio, Grijalba-2.

-

Qué son: Esferas de piedra precolombinas, talladas principalmente en gabro entre los siglos VI y XVI por sociedades cacicales.

-

Tamaños: Desde pocos centímetros hasta más de 2,5 metros de diámetro; pesos de cientos de kilos a varias toneladas.

-

Cómo verlas: Visite los sitios arqueológicos con guías locales y museos de la zona; algunas esferas también están en parques y edificios públicos del país.

-

Consejo: Llegue temprano o al atardecer; la luz rasante revela el pulido y las pequeñas irregularidades, como si la piedra hablara en relieve.

Nota del autor

Este artículo no ofrece una solución final. Ofrece, más bien, una invitación: aceptar que hay piedras que saben más que nosotros, y que aprender su idioma requiere el gesto más difícil de nuestra época—parar. En ese gesto, quizá, Costa Rica nos regala su enigma más redondo.

I. Szept w dżungli (KOSTARYKA).

Gdy zapada wieczór w delcie Diquís, powietrze gęstnieje od insektów i słodkiego zapachu bananowców. Między niską mgłą widać cienie, które nie należą do drzew. Są okrągłe, dokładne, milczące. Nie powstały z kaprysu rzeki ani z dawnego trzęsienia ziemi. To kule. Setki kamiennych kul — jedne wielkości piłki, inne jak mały samochód — wypolerowane do uporu. Nikt nie wie z całą pewnością, dlaczego tu są.

Kostaryka, kraj wulkanów i kawowców, skrywa na swym dalekim południu historię, która czasem brzmi jak zmyślenie. Pierwsze współczesne wieści o kulach pojawiły się pod koniec lat 30. XX wieku, kiedy brygady torujące drogę plantacjom bananów natrafiły na idealne głazy, w połowie zakopane, ułożone w linie ginące w sitowiu. Mówiono na nie „bolas” i odsuwano ciężkim sprzętem, nie podejrzewając, że popychają stulecia pamięci. Niektóre pękały, inne przetaczano do prywatnych ogrodów lub na miejskie place. Najszczęśliwsze zostały tam, gdzie się narodziły, jak bazaltowe oczy, które nie mrugają.

W tym miejscu czytelnik zechce wiedzieć: kto je zrobił? jak osiągnięto taką perfekcję? co znaczyły? Tajemnica zaczyna się od niewielu rzeczy, które możemy stwierdzić na pewno. Wiemy, że ich wytwórcami były wodzostwa Diquís — złożone społeczeństwa, które rozkwitały między VI a XVI stuleciem. Wiemy też, że rzeźbiono je przede wszystkim w gabro — skale twardej jak cierpliwość — a w mniejszym stopniu w piaskowcu i granodiorycie. Lecz poza techniką sfery zdają się wymykać, z dawną elegancją, posłuszeństwu wyjaśnień.

II. Geometria niemożliwego

Wyobraźmy sobie rzemieślnika sprzed tysiąca lat, który trzyma kamienny młot naprzeciw ciemnego bloku wydobytego ze wzgórz. Nie ma metalu, nie ma stalowych bloczków, nie ma tokarki. Jest za to czas. Dużo czasu. Uderzać, odłupywać, obracać; trzeć mokrym piaskiem, aż powierzchnia odda szorstkość. Niektórzy badacze sugerują użycie twardych rdzeni do „peckingu” — systematycznego obtłukiwania — i rzecznych abrazów do polerowania, być może z zastosowaniem ciepła, by kruszyć mikro-niedoskonałości. To proces bez skrótów. Kula jest formą najbardziej wymagającą: każdy nadmiar, każde niedopatrzenie zdradza rękę.

A jednak wiele kul zachowało kulistość ocierającą się o obsesję. Największe przekraczają dwa i pół metra średnicy i ważą tyle ton, że ich samo przemieszczenie wymaga organizacji, logistyki i celu. Odsłania się tu kolejny sekret: kule z zasady nie stały samotnie. Wykopaliska mówią o zespołach, o kilometrowych kręgach, o liniach wskazujących precyzyjne kierunki. Czy były mapami nieba? osiami władzy? znacznikami terytorium? instrumentami porządkującymi świat?

Geometria nie jest niewinna. Okrąg wyrysowany w ziemi przywołuje i porządkuje. Kula ustawiona przed domem wodza komunikuje coś, co każdy przybysz pojmie bez słów: tu jest hierarchia. Tu znajduje się centrum. Tu — powiedzieliby kronikarze, gdyby zdążyli — ogniskuje się wspólnota.

III. Alineacje i milczenia

III. Alineacje i milczenia

Do dziś, gdy dociera się do Finca 6, Batambal, El Silencio czy Grijalba-2 — stanowisk na dalekim południu, które chronią kule w ich pierwotnym kontekście — czuć zamysł, który nie daje się złożyć na karb przypadku. Kamienie, częściowo zakopane, zdają się wyłaniać z ziemi jak zastygłe pęcherzyki. Ustawiają się względem konkretnych wzgórz albo biegu słońca w oznaczonych momentach. Nie jest bezzasadne myśleć o kalendarzach, choć nauka domaga się ostrożności: są alineacje, tak; są wzory, tak; ale przełożyć te wzory na kalendarz solarny wymaga troski, którą zapewnią tylko czas i kolejne odkrycia.

Tymczasem — cisza. Diquís — nazwa pochodzenia keczua, która przylgnęła do rzeki Térraba niczym obcy pogłos — zachowuje muzykę wody i ptaków, czyniąc wiarygodną hipotezę ceremonii. A jeśli kule były punktami zgromadzeń? Jeśli wyznaczały procesje? Jeśli ich kolistość miała naśladować pełnię kosmosu, domykać dialog nieba z ziemią? W wielu kulturach to, co okrągłe, wskazuje na sacrum, na całość, na brak krawędzi. Nie jest niedorzeczne przypuszczać, że tu było podobnie.

Lecz tajemnica ma też wymiar ludzki. Ile rąk, ile pokoleń zajęło wyrzeźbienie katalogu kul, które znamy? Ile nauk przekazano z warsztatu do warsztatu, ile technik zginęło w ogniu konkwisty, ile opowieści snuto wokół tych kamieni, gdy noc mniej rozpraszała? Być może tu tkwi ich magnetyzm: gdzie jest kamień, jest cierpliwość. A gdzie jest cierpliwość, rodzi się opowieść.

IV. Złoto w środku: legendy i rany

Perfekcja kusi. W pierwszej połowie XX wieku legenda, że w kulach skryto złoto, rozniosła się jak wilgotny proch. Jedni rozbijali je młotami, inni wysadzali, jeszcze inni rozcinali z łatwością, z jaką łamie się milczenie. W środku, rzecz jasna, była tylko skała. Każda blizna opowiada historię napaści. Widok pękniętej kuli to jak patrzeć na mapę ludzkiej chciwości.

To nie jedyna rana. Wiele kul przewieziono — jedne do miast, inne na prywatne podwórza — gdzie zmieniły sens: z sakralnych punktów odniesienia stały się ozdobami. Dystans między tymi dwoma losami streszcza nasze nowoczesne zagubienie. Za każdym razem, gdy święty przedmiot ląduje między donicami, nie przedmiot się degraduje; to my — zgubiliśmy instrukcję jego czytania.

Na szczęście kraj stopniowo godzi się ze swymi kamieniami. Istnieją muzea, które przywracają kontekst; społeczności, które strzegą; przepisy, które chronią. Przede wszystkim jednak pojawiają się pytania, które nie szukają anegdoty o skarbie, lecz głębszej opowieści: jak kule wpisują się w wielką historię południowych wodzostw? co mówią o zarządzaniu władzą, o wymianie, o astronomii empirycznej, o przedkolumbijskiej estetyce?

V. Ceremonia patrzenia

Kuli się nie czyta — na kulę się patrzy. Patrzeć znaczy uczestniczyć, choćby nie w swoim czasie, w ceremonii, dla której ją stworzono. Podchodząc bliżej, widzimy, że nie jest absolutnie doskonała; dostrzegamy niewielkie płaszczyzny, dawne ślady uderzeń, bardziej chropowate fragmenty. Współczesne oko, przyzwyczajone do przemysłowej dokładności, odkrywa doskonałość trudniejszą: wystarczającą. Taką, która pozwala, by połysk chwytał światło, by krawędź rysowała ciągłą linię na tle zieleni, by objętość narzucała obecność bez słowa.

Stojąc przed nią, gość zawiera pakt. Kula obiecuje ciągłość — każdy punkt krawędzi przedłuża się w nieskończoną krzywiznę — i wymaga cierpliwości — jeśli chcesz coś zrozumieć, zostań chwilę, obejdź ją, poczuj skalę, posłuchaj insektów. W świecie, który pędzi, Diquís proponuje inne słowo: pozostać.

Może dlatego kule stały się — oprócz dziedzictwa — także etyką. W czasach pośpiechu przyjęcie okrągłej skały jako nauczycielki to nie byle co. Przypomina, że piękno bywa funkcją wytrwałości, a pamięć, gdy nie jest zapisana, potrzebuje bardziej upartych form, by przetrwać.

VI. Hipotezy w kręgu

VI. Hipotezy w kręgu

Archiwum teorii jest szerokie i czasem malownicze. Są takie, które widzą w kulach węzły nawigacji lądowej, linie widoczności między osadami, znaczniki funeralne. Inne mówią o zastosowaniach akustycznych, o rezonatorach rytuałów; miejska legenda, jakoby działały jak busole lub „traciły ciężar” przy pewnych pełniach, choć literacka, nie ma dowodów. Najbardziej solidne hipotezy widzą w nich symbole prestiżu i władzy, włączone w place i zespoły architektoniczne wodzostw, być może z korelatami astronomicznymi. To znaczy: nie były tylko rzeźbami; rzeźba była częścią systemu.

Tak więc archeologia nie tyle rozwiązuje, co zawęża krąg. Dziś wiemy więcej o tym, gdzie stały i z czego je wykonano, niż o ich ostatecznym „po co”. I może to najlepsza wiadomość: tajemnica nie jest dziurą — jest horyzontem.

VII. Język sfery

Gdybyśmy mogli przetłumaczyć głos kamienia, co by powiedział? Może opowiedziałby o pochodzeniu materii: gabro stygnące powoli pod wulkanem, dźwignięte potem na grzbiet świata ku światłu. Może opowiedziałby o dłoniach, które szukały go w górach, toczyły na pniach i linach ścieżkami, których już nie ma. Może zaśmiałby się z nas — tak przekonanych, że wszystko musi mieć natychmiastową użyteczność — i poprosił o popołudnie bez telefonów, by spróbować rzeczy oczywistej: być obok.

W kuli jest język, który rozpoznajemy, choć go nie studiowaliśmy: język pełni. W społeczeństwach, które mierzyły się z morzem, dżunglą i wulkanem, zbudowanie formy negującej przypadek to gest potężny. Kula potwierdza to, co się nie zmienia, nawet gdy otoczenie jest czystą zmiennością. To komunikat o porządku pośród chaosu, kamienny kwiat, który nie więdnie.

VIII. Powrót na miejsce

Kto chce usłyszeć ten język, powinien jechać na południe. Nie wystarczy zobaczyć kulę przeniesioną na miejski plac; trzeba stanąć w błocie, które ją otacza w jej własnym domu. W Finca 6 archeologiczne ślady domostw i placów towarzyszą kamieniom, przywracając im chór, który utraciły. W Batambal otwarty pejzaż pozwala zrozumieć skalę gestu: na tak rozległej równinie jak nie szukać znaków dla „nas”?

Podróż nie jest tylko geograficzna. Wymaga przesunięcia wewnętrznego: przejścia od chęci „wyjaśnić wszystko” do cierpliwości „zrozumieć coś”. W tym przejściu tajemnica się nie rozprasza; staje się towarzyszką. A kula, która zdawała się niema, okazuje się dyskretną nauczycielką.

IX. Epilog: czego jeszcze nie wiemy

Być może nasza epoka — tak zakochana w odpowiedzi — niecierpliwi się wobec tego, czego nie da się domknąć. Ale są tajemnice, które warto ocalić, nie z ignorancji, lecz z szacunku. Kule z Diquís uczą, że przeszłość może być dokładna, nie będąc przejrzystą; że piękno może odmówić bycia pożytkiem; że zaginiona wspólnota wciąż może dyktować lekcje formy i sensu.

Gdy słońce zachodzi i cienie wracają do drzew, kule zostają, oddychając swoim milczeniem. Jutro byłoby dla nich wczoraj. I pojutrze również. Spójrz raz jeszcze: zdają się poruszać, gdy odchodzi światło. Oczywiście się nie poruszają; to my — wreszcie zaczynamy obracać się w ich rytmie.

Ramka: informacje dla ciekawego podróżnika

-

Gdzie: Delta Diquís, kanton Osa, południe Kostaryki. Kluczowe stanowiska: Finca 6, Batambal, El Silencio, Grijalba-2.

-

Czym są: Przedkolumbijskie kamienne kule, rzeźbione głównie w gabro między VI a XVI wiekiem przez społeczności wodzowskie.

-

Rozmiary: Od kilku centymetrów do ponad 2,5 metra średnicy; waga od setek kilogramów po wiele ton.

-

Jak je zobaczyć: Odwiedź stanowiska archeologiczne z lokalnymi przewodnikami i muzea regionu; niektóre kule znajdują się także w parkach i budynkach publicznych kraju.

-

Wskazówka: Przyjedź o świcie lub o zmierzchu; niskie światło odsłania poler i drobne nieregularności, jakby kamień mówił reliefem.

Notatka autora

Ten tekst nie oferuje ostatecznego rozwiązania. Proponuje raczej zaproszenie: przyjąć, że są kamienie, które wiedzą więcej od nas, a nauczenie się ich języka wymaga najtrudniejszego gestu naszych czasów — zatrzymania się. W tym geście być może Kostaryka daje nam swoją najbardziej okrągłą zagadkę.

I. A rumor in the jungle

At dusk in the Diquís delta, the air thickens with insects and the sweet scent of banana. In the low mist there are shadows that don’t belong to the trees. They are round, exact, silent. They are not the whim of a river or an ancient earthquake. They are spheres—hundreds of stone spheres, some the size of a ball, others like a small car, polished to the point of stubbornness. No one knows for certain why they are there.

Costa Rica, a country of volcanoes and coffee, keeps in its far south a story that sometimes feels invented. The first modern notices of the spheres emerged in the late 1930s, when crews opening paths for banana plantations stumbled upon perfectly shaped rocks half-buried, laid out in alignments that vanished into the reeds. They called them “bolas” and pushed them aside with machinery, unaware they were shoving centuries of memory. Some cracked; others were rolled to private gardens or city squares. The luckiest remained where they were born, like basalt eyes that never blink.

By now the reader will want to know: who made them? how did they achieve such perfection? what did they mean? The mystery begins with the little we can state for certain. We know their manufacture belongs to the Diquís chiefdoms, complex societies that flourished between the 6th and 16th centuries. We also know they were carved mostly from gabbro—a rock as hard as patience—and to a lesser extent from sandstone and granodiorite. But beyond the technical, the spheres seem to resist, with an old-fashioned elegance, the obedience of explanations.

II. The geometry of the impossible

Imagine an artisan a thousand years ago holding a stone hammer before a dark block quarried from the hills. There are no metals, no steel pulleys, no lathe. There is, instead, time. A great deal of time. Strike, chip, turn; rub with wet sand until the surface gives up its roughness. Some researchers propose that hard cores were used for “pecking”—systematic chipping—and river abrasives for polishing, perhaps applying heat to fracture micro-imperfections. It’s a process that allows no shortcuts. The sphere is the most demanding form: any excess, any lapse, betrays the hand.

And yet many spheres retain a sphericity bordering on the obsessive. The largest exceed two and a half meters in diameter and weigh so many tons that moving them at all demands organization, logistics, and purpose. Here another secret appears: the spheres were not, as a rule, alone. Archaeological finds speak of ensembles, kilometer-wide circles, alignments pointing to precise directions. Were they maps of the sky? Axes of power? Territorial markers? Instruments to order the world?

Geometry is not innocent. A circle drawn on the ground calls and orders. A sphere installed before a chief’s house announces something any visitor understands without words: here there is hierarchy. Here there is a center. Here—chroniclers would have said, had they arrived in time—a community is articulated.

III. Alignments and silences

III. Alignments and silences

Even today, when you arrive at Finca 6, Batambal, El Silencio, or Grijalba-2—sites in the far south that safeguard spheres in their original context—you sense an intentionality that cannot be chalked up to chance. The stones, half-buried, seem to emerge from the earth like frozen bubbles. They align toward specific hills or toward the sun’s path at marked moments. It’s not far-fetched to think of calendars, though science keeps asking for caution: yes, there are alignments; yes, there are patterns; but turning those patterns into a solar calendar requires a care that only time and more finds will guarantee.

Meanwhile, silence. Diquís—a Quechua name that stuck to the Térraba River like a foreign echo—keeps a music of water and birds that makes the hypothesis of ceremony feel reasonable. What if the spheres were gathering points? What if they marked processions? What if their circularity sought to imitate the completeness of the cosmos, to seal a dialogue between sky and earth? In many cultures, the round points to the sacred, the whole, the edgeless. It isn’t unreasonable to suppose the same here.

But the mystery is not only cosmological. It is also human. How many hands, how many generations did it take to carve the catalogue of spheres we know today? How many lessons passed from one workshop to another, how many techniques vanished in the fires of the conquest, how many stories were told around these stones when the night was less distracted? Perhaps their magnetism lies there: where there is stone, there is patience. And where there is patience, there is story.

IV. Gold inside: legends and wounds

IV. Gold inside: legends and wounds

Perfection tempts. In the first half of the 20th century, the legend that the spheres held gold within spread like damp gunpowder. Some opened them with blows, others dynamited them, others split them with the same ease with which silences are broken. Inside, of course, there was only rock. Every scar tells the story of an assault. To see a cracked sphere is like looking at a map of human greed.

It isn’t the only wound. Many spheres were moved—some to cities, others to private yards—where their meaning changed: from ceremonial markers they became ornaments. The distance between those two fates sums up our modern bewilderment. Whenever a sacred object ends up among flowerpots, it isn’t the object that is degraded; it is us, who lost the manual for reading it.

Fortunately, the country has been making peace with its stones. There are museums that return them to context, communities that guard them, laws that protect them. There are, above all, questions that no longer seek the anecdote of treasure but the deeper weave: how do the spheres fit into the grand history of the southern chiefdoms? what do they tell us about the management of power, about exchange, about empirical astronomy, about pre-Columbian aesthetics?

V. The ceremony of looking

A sphere isn’t read; it’s looked at. And to look at it is to take part, however belatedly, in the ceremony for which it was made. You draw near and confirm it isn’t absolutely perfect; you discover tiny planes, ancient impact marks, rougher zones. The modern eye, accustomed to industrial exactitude, finds a harder perfection: the sufficient perfection. The kind that is enough for the surface shine to catch the light, for the edge to draw a continuous line against the green, for the volume to impose its presence without saying a word.

Before it, the visitor enters into a pact. The sphere promises continuity—every point of the rim extends into an unending curve—and demands patience—if you want to understand anything, you’ll have to stay a while, walk around it, feel its scale, listen to the insects. In a world that runs, Diquís proposes a different verb: to stay.

Perhaps that is why the spheres have become, besides heritage, an ethic. In hurried times, accepting a round rock as a teacher is no small thing. It reminds us that beauty can be a function of constancy and that memory, when it isn’t written, needs more stubborn forms to survive.

VI. Hypotheses in a circle

The archive of theories is ample and sometimes picturesque. Some place the spheres as nodes of overland navigation, as lines of sight between settlements, as funerary markers. Others suggest acoustic uses, as resonators for ritual; the urban myth that they act like compasses or “lose weight” under certain full moons—literary as it is—lacks evidence. The most solid hypotheses situate them as symbols of prestige and power, integrated into plazas and architectural ensembles of the chiefdoms, perhaps with astronomical correlates. That is: they were not merely sculptures; the sculpture was part of a system.

Archaeology thus does not so much resolve as tighten the circle. Today we know more about where they stood and what they were made of than about their ultimate “why.” And perhaps that’s the best news: a mystery is not a hole; it’s a horizon.

VII. The language of the sphere

If we could translate the stone’s voice, what would it say? Perhaps it would tell of the matter’s origin: gabbro slowly cooled beneath a volcano, then hoisted on the world’s back toward the light. Perhaps it would tell of the hands that sought it in the hills, rolled it on logs and ropes along paths that no longer exist. Perhaps it would laugh at us—so convinced that everything must have an immediate use—and ask for an afternoon without phones to attempt the obvious: to be beside it.

In the sphere there is a language we recognize without study: the language of wholeness. In societies that faced sea, jungle, and volcano, building a form that denies accident is a powerful gesture. The sphere asserts what does not change, even when the surroundings are pure change. It is a message of order amid chaos, a stone flower that never withers.

VIII. Return to the site

Whoever wants to hear that language must go south. It isn’t enough to see a sphere moved to a city square; you have to set foot in the mud that surrounds it in its original home. At Finca 6, for instance, the archaeological traces of dwellings and plazas accompany the stones, returning to them the chorus they had lost. At Batambal, the open landscape allows you to grasp the scale of the gesture: in so vast a plain, how could one not look for marks of the “we”?

The journey is not only geographic. It demands an inner shift: to move from the urge to “explain everything” to the patience to “understand something.” In that passage, the mystery does not dissolve; it becomes a companion. And the sphere, which seemed mute, turns into a discreet teacher.

IX. Epilogue: what we don’t know (yet)

Perhaps our age—so in love with answers—grows impatient with what cannot be closed. But there are mysteries worth preserving, not out of ignorance but out of respect. The Diquís spheres teach that the past can be exact without being transparent, that beauty can refuse to be utility, that a vanished community can still dictate lessons in form and meaning.

When the sun sets and the shadows again belong to the trees, the spheres remain, breathing their silence. Tomorrow would have been yesterday to them. And the day after tomorrow as well. Look again: they seem to move when the light goes. They don’t, of course; it’s us, finally beginning to turn at their pace.

—

Sidebar: facts for the curious traveler

Where: Diquís Delta, Osa canton, southern Costa Rica. Key sites: Finca 6, Batambal, El Silencio, Grijalba-2.

What they are: Pre-Columbian stone spheres, carved mainly from gabbro between the 6th and 16th centuries by chiefdom societies.

Sizes: From a few centimeters to over 2.5 meters in diameter; weights from hundreds of kilos to several tons.

How to see them: Visit the archaeological sites with local guides and the region’s museums; some spheres also stand in parks and public buildings around the country.

Tip: Arrive at dawn or at dusk; raking light reveals the polish and tiny irregularities, as if the stone spoke in relief.

—

Author’s note

This article offers no final solution. It offers, rather, an invitation: to accept that there are stones that know more than we do, and that learning their language requires the hardest gesture of our era—to stop. In that gesture, perhaps, Costa Rica gives us its roundest enigma.